Multimedia meeting report: Health systems that transform gender norms

On the 28 February an international group of gender and health systems experts came together in Nairobi for a dialogue with their counterparts from the policy world. The meeting was an opportunity to look across domains of the health system that included community health, governance and access to services to identify how gender norms impede progress of the development of health systems which are people-centred and truly universal. The meeting was convened by the KEMRI Wellcome Trust, supported by RinGs and funded by the ALIGN Platform.

The meeting grew out of a growing body of research at KEMRI Wellcome Trust that addresses issues like governance, child health, nutrition, household decision making and financing from a gender perspective, capacity building to strengthen a gender analysis and a desire to engage with government action in this area. As part of this KEMRI Wellcome Trust have been active leaders in RinGs – an international network which has been supporting researchers in low- and middle-income countries to better study and communicate about this area of work.

Inspiring opening from @KuiMuraya of @KEMRI_Wellcome @RinGsRPC, who reminds us that #healthsystems are shaped by and contribute to #gendernorms, but there is little attention to the gendered nature of health systems. We’re here to help change that. @ALIGN_platform pic.twitter.com/EOGHS5Ad02

— Suzanne Petroni (@suzp) February 28, 2019

Further reading

The view from researchers

An opening presentation from Valerie Percival outlined our expanding knowledge of how health systems are both shaped by and shape gender norms, mirroring broader inequity in society. She argued that health systems should provide egalitarian spaces for the engagement of all and promote gender equity. Our work in this area should explore how gender equity should be supported while guarding against negative backlash.

Valerie highlighted that traditional models assume that health systems are gender neutral and they don’t acknowledge the role of social norms in provider behaviour, access to services, medicines and commodities, governance, human resource management and other aspects that are central to health systems building blocks. As they are social systems, health systems software is also shaped by the norms of the societies that they are situated within, for example reinforcing problematic norms about women’s role in unpaid care. Governance structures are dominated by men with little effort to support women. Health systems engage in discriminatory actions towards women and fail men and boys in multiple ways. Furthermore, there is scepticism about whether these systems can change and too often women (including female health workers) are tasked with taking responsibility for changing the world without adequate support and acknowledgement.

But change is possible.

Efforts to tackle gender norms need to take account of neo-colonial histories and must be built in the countries involved. People in the countries under consideration need an opportunity to share knowledge and shape and lead the agenda.

Further reading

The view from policy makers

Dr Mary Nandili, the Director of Nursing Services in the Kenyan Ministry of Health, explored how gender affects women’s leadership in the health system – including the ratio of women to men and the ways in which social norms have led women to be seen as the ‘helpers of men’.. In Kenya, women were traditionally found in positions related to nursing, nutrition and other therapy areas. Now, however, women are competing for the same roles as men. She argued that from 2000 onwards Kenya began to significantly increase the number of women in leadership positions and dramatically increased their influence. The gender gap has narrowed which has led to stronger leadership with more harmonious working relationships and more effective management.

Dr Joyce Mutinda, Chairperson of the National Gender & Equality Commission (NGEC), Kenya, provided insight into how law, policy and standard setting can be used to support progress towards gender and other forms of equity, inclusion and raising the power of the downtrodden. She called for health policy that is devoid of gender stereotypes, and care that policy does not further marginalise disadvantaged groups. While the constitution offers protections in relation to health this does not translate into health for all. Ensuring this is particularly difficult in the context of devolution where county governments may lack the ability to budget effectively for this, when minorities are excluded for example in remote and insecure areas, and disabled people do not have adequate access to services. She argued that gender is not about women, it is about everybody. People need to be sensitised about their rights so that they can claim them, and there is a need to comprehensively mainstream gender in the health sector to address inequality in access to services, improve quality, increase resource allocation and support the adoption of effective monitoring systems.

“Speak it out. Let’s learn from each other to make health systems friendly and responsive to all people including minorities.”

Dr Joyce Mutinda

‘My work is to fight’ says Dr Joyce Mutinda, Chairperson of Kenya’s National Gender and Equity Commission. What an amazing woman, challenging us to find ways to transform health systems to be gender equitable. #gendernorms #healthsystems @RinGsRPC— linda waldman (@linda_lindaw) February 28, 2019

Access to services for marginalised groups

The view from researchers

Rachael Rebecca Apolot explained how in Uganda a community scorecard project on maternal health highlighted how women with walking disabilities faced difficulties in accessing services and unaddressed psychosocial needs. Services were physically inaccessible with steps, chairs and beds that were too high and toilets in which women had to crawl on the dirty floor. Transporters were reluctant to carry women to the health centre and over-charged disabled women. Having to travel to the health centre with a carer increased the costs of transport. Women were often aggressively questioned by health workers about their sexuality. This was underpinned by the norms that disabled women should not have a sexual life or have children. Community norms led to their marginalisation – as people thought that they may curse them. Discriminatory attitudes in the health system added to the troubles of women who were dealing with discriminatory norms in other areas of their lives.

Chandani Kharel explored gender in the workings of the Health Facility and Operation Management Committees of Nepal. These committees were set up to ensure community participation in primary health care. While these committees were able to recognise marginalised groups (such as women and Dalits) their workings were still subject to social hierarchies and gendered norms that impeded their function. Women’s representation was often tokenistic which emphasizes the need to foster true inclusion.

Returning to Uganda, gender norms also impeded access to maternal health services for migrant women from communities of labourers on sugar cane plantations. Richard Mangwi explained how his research explored how social norms prevented migrant women seeking timely care, as they were told that bearing the pain of labour without making a fuss was a sign of strength. In health care settings anti-migrant sentiment and women’s inability to speak the local language were a barrier to accessing services.

Why would migrant women “resist” being referred to facilities for appropriate maternal health care? asks @mangwi @RinGsRPC & @KEMRI_Wellcome meeting in Nairobi pic.twitter.com/R2DhZN7WAD— Sarah Ssali (@sssalie) February 28, 2019

Speaking from the Kenyan perspective Chi-Chi Undie argued that every client has a gender identity and this shapes the nature of access to services by opening up or constraining opportunities. Her focus was on children and young people seeking services for sexual and gender-based violence. Children are constructed as vulnerable and this can improve service access. However, it may mean that children have to be accompanied by their parents – even when they would rather see a health professional alone. She talked about how violence against children and violence against women are often linked. Mothers may have experienced violence themselves or may require psychological assistance if their children have been hurt. In addition, social norms prescribe that even within the health system, mothers are required to lead in a caring role which is a further burden upon them. This points to the importance of an integrated and sensitive approach to care related to sexual and gender-based violence.

The view from the audience

A gender lens is important in considering the needs of all people including those not generally thought to be disadvantaged such as male migrants. We need to consider gender norms because they help shine a light on the areas we have neglected. For example, it is assumed that men don’t need services, however many fail to seek care because of norms around masculinity. Sometimes people don’t seek care because of provider behaviour which is directly related to gender norms. If we don’t consider gender norms we will fail to achieve Universal Health Coverage and we will leave some sections of the population behind.

Adolescents, by virtue of their age, face barriers in access to services – highlighting the intersection gender and age. They have to go to school and services are not always friendly or designed to meet their needs. Responsive health systems need to consider gender because the way boys access health services is different to girls as a result of norms and socialization. The health system tries to create safe spaces for adolescents, but this may keep them separate from other people and add to the vulnerability and stigmatisation that they face.

The urban poor have systems of authority and accountability that are separate to the state; for example, there are gangs, informal providers etc. These systems can stop people accessing the services that they require. Often the urban poor are seen as a problem and lack appropriate legal statuses which in turn contributes to a lack of state accountability for their rights. We need to think beyond clinical services to how environmental hazards, a lack of sanitation and living in ‘legal grey areas’ affect their health needs.

Community health systems

The view from researchers

Lilian Otiso led us through research that implemented quality improvement in various counties in Kenya. She noted that the tools that Community Health Volunteers are equipped with do not adequately enable them to consider issues of gender and other variables such as age.

Through their work with maternal and child services they identified instances where Community Health Volunteers helped challenge norms. For example, their teams realised that adolescent mothers had difficulties in accessing services because of poor provider attitudes, and that older women were served first ion health facilities. They subsequently created special referral cards for them and worked with health centre staff to make services more welcoming for the young mothers. The Community Health Volunteers noted that in certain cases, men were the household heads as well as the primary carers. They supported one man, for example, to take his four children to the health centre which he didn’t know he was allowed to do because primary health facilities are generally regarded as ‘women’s spaces’. The Community Health Volunteer helped him to feel comfortable with this and as a result his children were immunised and treated for undernutrition.

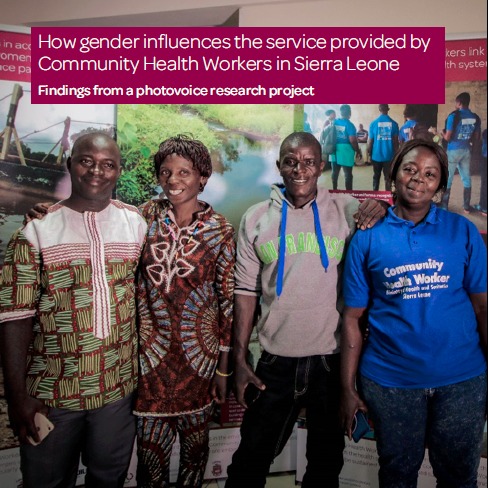

Sally Theobald presented work by Haja Wurie and others in Sierra Leone. They found that there was a heavy investment in hiring Community Health Workers post-Ebola to rebuild trust between the community and the health system. Nonetheless, gender norms affected who was trained as a Community Health Worker. Although the government deliberately tried to recruit women because they wanted workers who could respond to maternal health needs, more men got employed as they were more likely to have the appropriate level of education. Also, women faced challenges in blending community, paid and domestic work and some husbands didn’t allow their wives to do the job. Community Health Workers are strategically placed to alter gender norms but are also subject to them themselves as they are part of the community within which they are working.

In Uganda David Musoke’s work uncovered that although the role of community health workers was supposed to be gender neutral, in fact, they conformed to gender norms in the ways that they delivered their tasks. Men did the emergency work, transportation and physical work such as ditch digging. They had access to motorbikes whereas the female CHWs did not. Women were more involved in the maternal health work and were more available in the community as they spent more time in the home when men were out working. David also discussed the need to take into account the gender of Community health Worker in the design of community health programmes, as people often want to see a provider of the same sex.

Dr. David Musoke discussing photovoice as a tool discuss gender norms in community health systems. @DavidMusoke14 pic.twitter.com/CJYMUifovw— RinGs (@RinGsRPC) February 28, 2019

Presentations by both Sally (on behalf of Haja) and David additionally highlighted the utility of innovative research methods and approaches such as use of the Photovoice technique which ‘tell the story’ from the perspective of community members. Such participatory approaches that are fundamentally about co-production of knowledge.

Further reading

- How gender influences the services of community health workers in Sierra Leone

- Reflecting strategic and conforming gendered experiences of community health workers (CHWs) using photovoice in rural Wakiso district, Uganda

- Gender and Community Health Worker programmes in fragile and conflict-affected settings. Findings from Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Liberia

The view from policy makers

Ms Charity Tauta, Deputy Head of the Community Health and Development Unit in the Ministry of Health, Kenya, argued that meetings like this are very important for policy makers who are considering how to get to Universal Health Coverage. She explained that the community health policy will be reviewed later in the year and that evidence on gender will be welcomed in finalising it. She felt there was an assumption that women were better carers as they appear to be more caring, more available and more spiritual. However, this needs to be unpacked. She quoted Professor Miriam Were of the University of Nairobi, who says, “If it’s not happening at the community, it’s not happening.” Action at community level is vitally important to the rest of the health system.

Charity Tauta, Deputy Head, Comm Health & Dev Unit, MOH at the @KEMRI_Wellcome and @RinGsRPC #gendernorms and #healthsystems meeting. There is need for us to bridge the gap between researchers and policy makers. pic.twitter.com/BgrZOwvNC7— Kui Muraya (@KuiMuraya) February 28, 2019

The view from the audience

To improve gender responsiveness and allow Community Health Workers to reach those who are marginalised it would be good if they could go to venues other than households such as schools and workplaces. Talking in the household can be difficult sometimes, particularly for adolescents. In Sierra Leone they do go to the market place and in Kenya they go to schools and day care centres in urban slums.

There is a need in Kenya to increase the numbers of volunteers for adequate coverage. Community Health Volunteers in Kenya are selected by their fellow community members based on trust and perceived ability to manage health issues. However, since devolution it is unclear how much support and capacity development are being provided to them and this should be evaluated. The issue of volunteerism and free labour which is expected from Community Health Workers/Volunteers was also raised by the audience and the need to consider including them in the government payroll.

It was thought that supportive, problem-solving supervision would help Community Health Workers/Volunteers to overcome their own negative attitudes, for example towards adolescents and better deal with gender norms.

Governance

The view from researchers

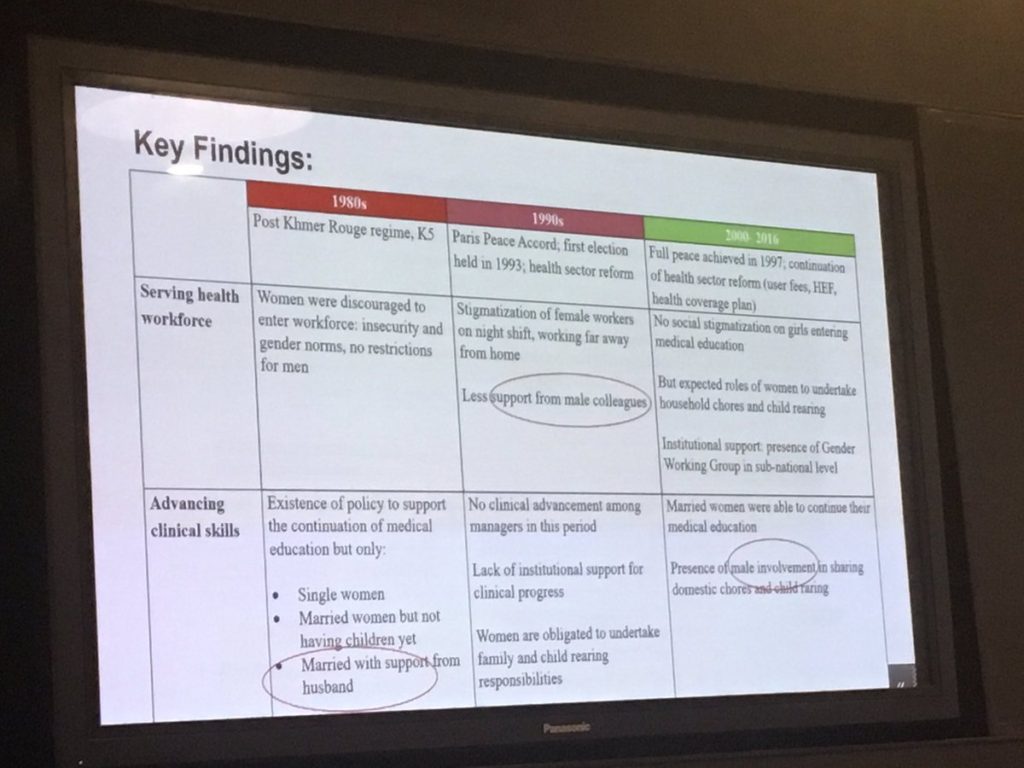

Sreytouch Vong led us through the results of her life histories work with women in the post-conflict Cambodian health system. She charted those factors that were supportive or undermining of their progression during that time. She found that if you want to support gender equality and progression for women into leadership positions, then male support is vital. This starts in the home with support to household chores and care giving for the young and the old. Female managers who have been supported by male supervisors early in their careers had made progress. However, in Cambodia many male managers still see gender as a woman’s issue and as a result they do not attend meetings that would build their skills in this area which is a weakness in the health workforce and policy planning process.

Male engagement very important for advancing women in leadership in health sector says @SreytouchVong #gendernorms #healthsystem pic.twitter.com/EpSjfiXQVf— RinGs (@RinGsRPC) February 28, 2019

Tumaini Nyamhanga spoke about gender mainstreaming in PMTCT policies in Tanzania. Mainstreaming involves making gender central and recognising gender-based constraints such as unequal ownership of resources, harmful gender norms, imbalances in power and finding measures to correct these. However, gender mainstreaming was inadequately applied in PMTCT policy documents and organisational practices at service delivery level where most were aware of gender imbalances but did not suggest any corrective measures to transform this. He suggested that leaders in the policy realm require training to make them more gender-responsive and contribute to formulation of gender-transformative policies.

Gender mainstreaming means considering gender in all policies says Dr. Tumaini Nyamhamga #gendernorms #healthsystems pic.twitter.com/BNq5iXiwKO— RinGs (@RinGsRPC) February 28, 2019

Chinyere Mbachu from Nigeria reported on her study of gender and health leadership where she found that both male and female health care managers had preconceived notions of men and women and this affected how they perceived leaders. Men believed that women don’t make good leaders because they are ‘emotionally unstable’ and lacking in focus. They also saw women as ‘followers’ and didn’t expect much from them. Even some female senior health care leaders shared these views. As a result, woman managers did not feel accepted or supported. The unequal distribution of power to men and these structures were therefore reproduced making it harder for women to occupy leadership positions in the future. Chinyere explained that when she initially started her study, her target respondents were senior healthcare managers. However, she could not identify a single woman in the senior health leadership because they simply weren’t there. As a result, she ended up conducting her study with mid-level healthcare managers so as to have both male and female respondents (as opposed to all-male respondents). This dearth of women in high-level health leadership positions in itself highlights the gendered nature of the health system, specifically the health workforce, where women generally occupy the ‘lower levels’ with their numbers sharply decreasing in the higher categories including the decision-making space.

Gendered perceptions and experiences of senior health care managers in Nigeria – Dr. Chinyere Mbachu #gendernorms #healthsystems pic.twitter.com/MM1yqBepwp— RinGs (@RinGsRPC) February 28, 2019

Further reading

- Leadership experiences and practices of South African health managers: what is the influence of gender? -a qualitative, exploratory study

- Promoting women’s leadership in the post-conflict health sector in Cambodia

- Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in Tanzania: assessing gender mainstreaming on paper and in practice

The view from policy makers

Dr Hannah Kagiri, Head of the Gender Unit in the Kenyan Ministry of Health, explained that gender mainstreaming in the Kenyan health sector is very young and still being institutionalised. While gender is acknowledged in policies there is a lack of understanding about how to translate this into practice; and knowledge of gender norms among policy makers is low. Gender equality is often equated with reproductive health and there is not much of a focus on the non-biological social determinants of health. This leads to gender-blind policies, non-responsive budgeting and governance decisions that are insensitive to gender. There is, therefore, a need for a clear understanding of gender concepts in the Ministry and at county level. The Kenya Health and Gender and Equality policy outlines what needs to be done including better disaggregated data for decision making. For instance, while tools to collect heath data are sex-disaggregated at the point of collection, this is often removed when data are inputted into the DHIS online system. In turn, this makes the creation of gender sensitive health indicators challenging. Furthermore, there is a need to lobby for a greater budget for the Unit.

Dr Hannah Kagiri, Head of Gender Unit, MOH discussing facilitators & barriers to gender mainstreaming in health in the @KEMRI_Wellcome and @RinGsRPC #gender and #HealthSystems meeting pic.twitter.com/nplHj2MmWJ— Kui Muraya (@KuiMuraya) February 28, 2019

The view from the audience

There is a need for researchers to build their skills in interacting with policy makers, for example in appropriately packaging research evidence to suit the needs of policy makers. However, the question was raised as to whether researchers are best-placed to perform this function, or whether we should engage ‘knowledge brokers’ to bridge the gap between researchers and policy makers. We also need to think about how to tell a ‘gender story’ to policy makers and others so that they can internalize the message, act on it and carry it forwards.

Policy is very bound up with politics, and development and implementation of gender-sensitive policies is often dependent on the good will of staff within the Ministry and government to make change happen. This speaks to the importance of fostering gender champions. Nonetheless many men have not been influenced by our ideas. Men need to take up this cause and support their female counterparts and help to think of effective strategies to promote gender equity. We also need to explain better how men are failed by harmful gender norms including negative masculinity and that their health suffers as a result.

Policy implications

“The policy implications of this work are complex and require concerted efforts. Recognizing this, the meeting was intended to be the start of a conversation about the way forward and building bridges rather than a solution to all the problems facing the health system. We shared across our different realms and agreed on some potential tools and interventions at different levels to achieve our vision. Evidence is crucial to the whole endeavour. We need to go beyond lip service and tokenistic approaches to change.”

Sally Theobald

Access to services: Much of the research presented clearly outlined how gender norms (and other forms of inequity) lead to exclusion from services which differs between contexts. Gender norms also shape how health care workers work and engage with patients and whether they can challenge values. We need to look at this from both a community and clinical services perspective.

Governance: In Kenya devolution has implications for the flow of money, power and resources and how these are used and negotiated for different people’s benefit. While the Gender Unit is supporting this work, we need to develop shared language and understandings throughout the health system.

Financing: Budgets need to be gender responsive. We should pay attention to gendered voluntarism at community level and which roles are paid and which are not paid. In terms of insurance we should consider who has access to it and what that means for access to health services at the county level.

Human resources: We heard about gender stereotypes around leadership and the interplay between gender, age, marriage, and professional cadre. To counteract this mentorship, supportive supervision and deconstructing a glass ceiling were suggested.

Health information systems: Gender sensitive health indicators and summary tools for disaggregation of data at local level and higher up the system are needed. But we also need the political will to use this data for change. Some of the qualitative methods used in the research presented such as in-depth interviews, life histories and photovoice can help augment this quantitative information.

Medical products and technologies: The norm for testing is often a male model, protective clothing used by health workers are designed for a male body and stock outs of essential medicines have differential impacts on men, women, boys and girls.

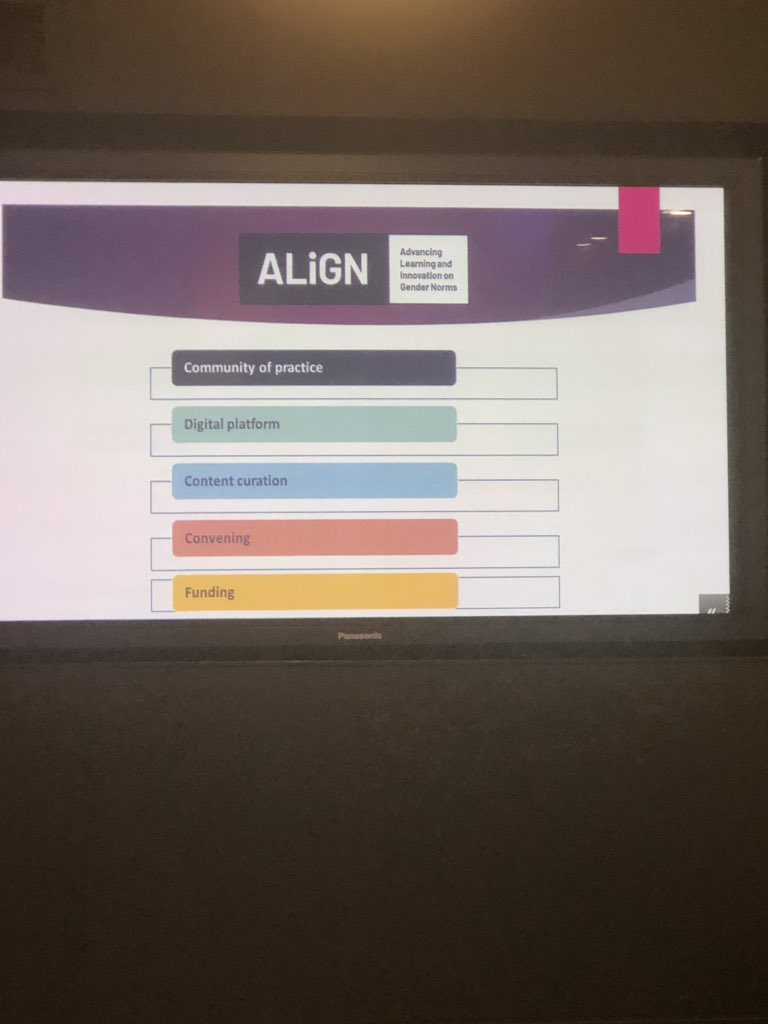

Learning about Advanced Learning and innovation on gender norms @suzp @ALIGN_platform. Very impressive!! @RinGsRPC @HERDIntl @KEMRI_Wellcome pic.twitter.com/k7Kg0m2pG5— Chandani.kharel (@ChandaniKharel) February 28, 2019

“Representing ALIGN, which funded the convening, I congratulate KEMRI Wellcome Trust, RinGs and the meeting participants for so thoughtfully advancing learning about a topic that has, to date, been insufficiently addressed in global health. Only by understanding the gendered nature of health systems can researchers, practitioners and policymakers overcome harmful gender norms, thereby achieving better health outcomes and improving opportunities for gender equity.”

Suzanne Petroni

Acknowledgements

This convening was funded by Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms (ALIGN), an initiative led by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). For further information, visit www.alignplatform.org and follow @ALIGN_Project.

This meeting report was written by Kate Hawkins and also draws on notes from Linda Waldman. Some of the photos in the brief were taken by Suzanne Petroni.

15/04/2019 @ 06:28

about women’s role in unpaid care. Governance structures are dominated by men with little effort to support women